Imaging Nuclear Family

Click here to view the work.

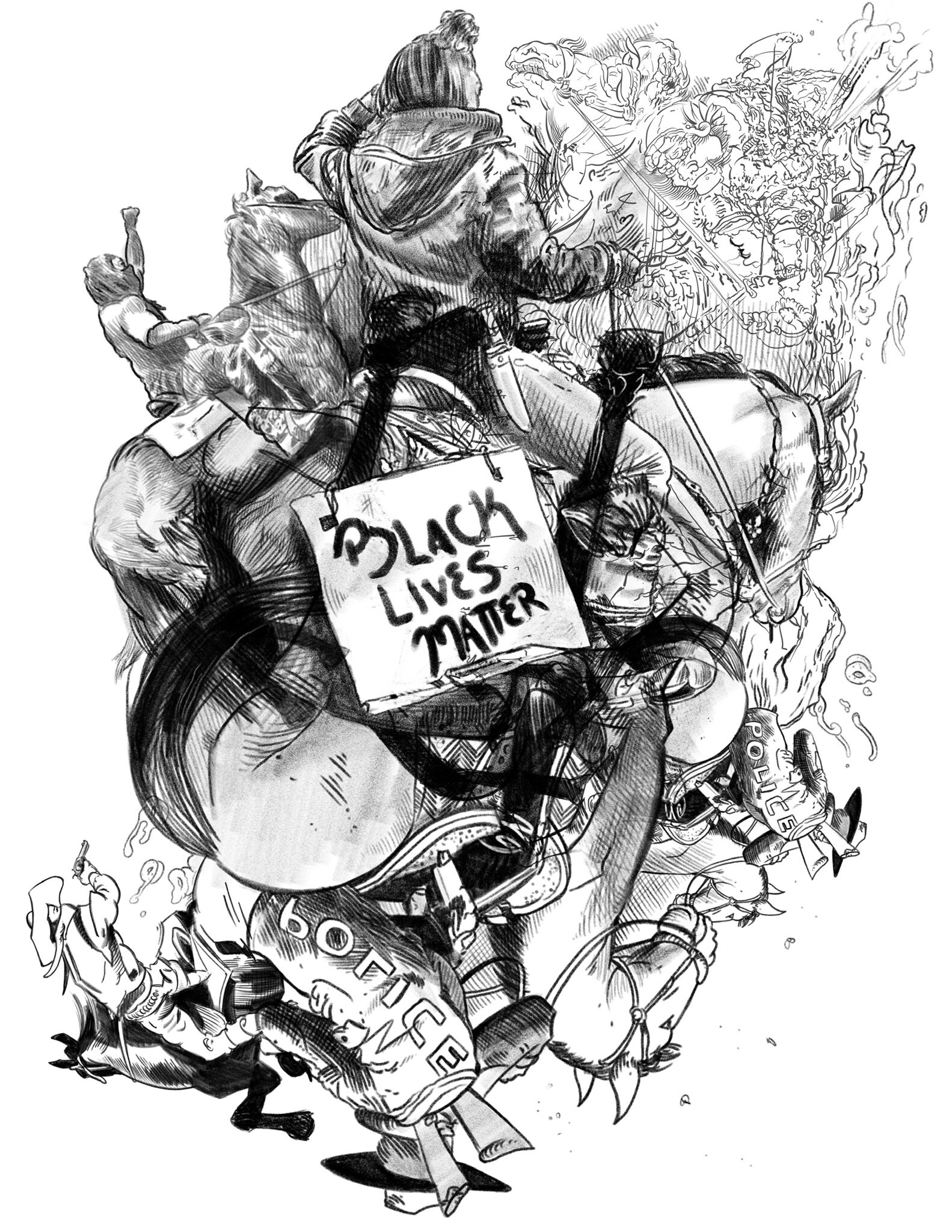

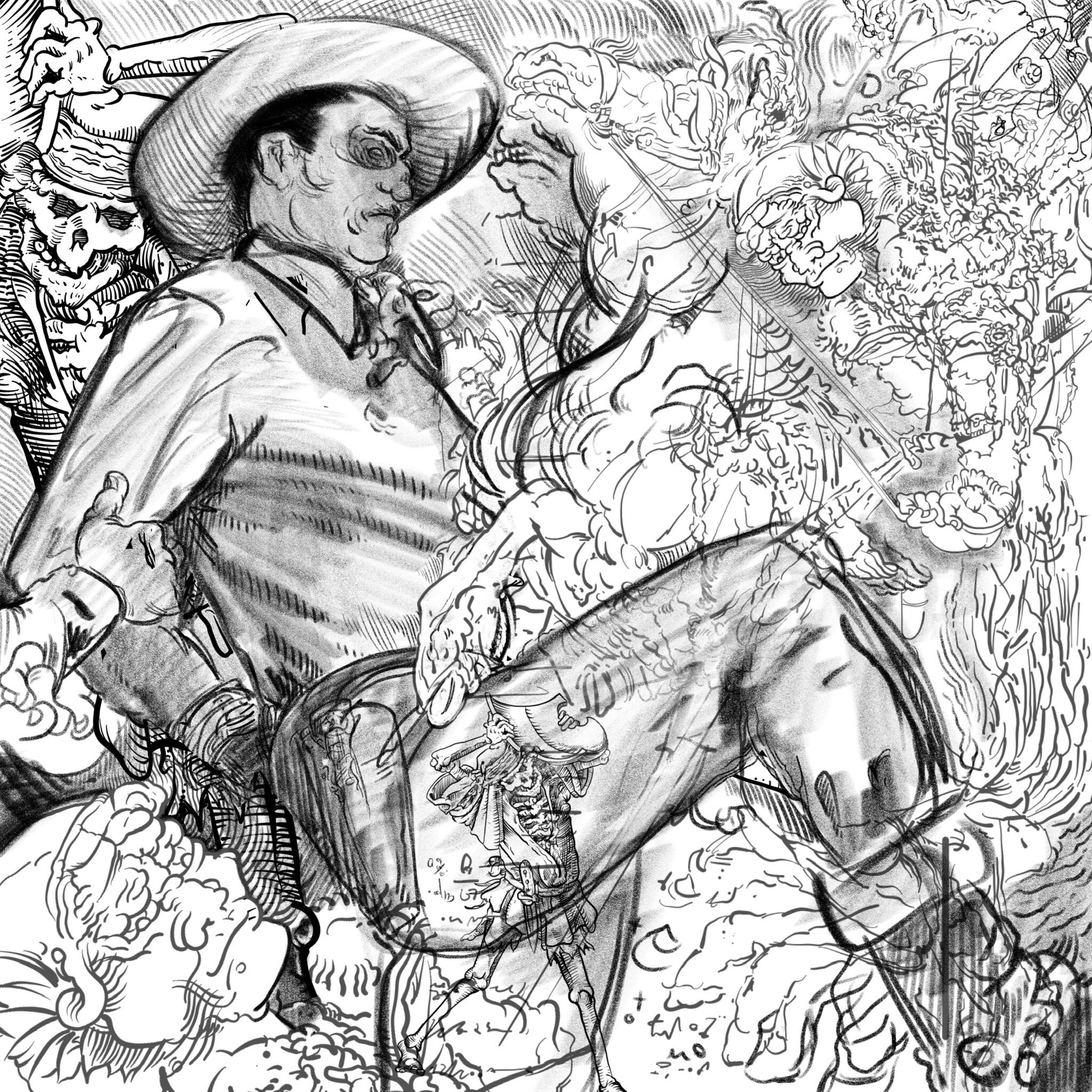

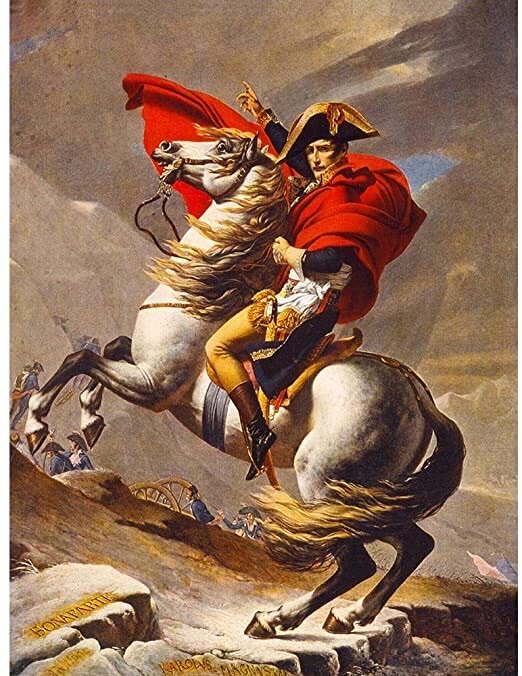

It is difficult to explain the nuance and complexity of family dynamics and dangerous to imply that any one family is even significantly like another without applying unnecessary judgement. This body of work focuses on work produced with the participants, Joel (myself), Emily, Ajax, Daisy, Leon, and Scout Hopler. Since 2018, we have integrated a practice of image generative collaborative visual communications. As we work, we discuss boundaries for both the work and each other to act out and learn respectful behavior. We make plans and then break them, encourage experimentation, then troubleshoot the work to balance the group’s aesthetic vision at the time. In producing these works, we have had a wide range of conversations. We have arguments about what we should do, cried about what has been done (or what the group decides not to let someone do), laughed at silly drawings, and seen the results of individuals working in secret. It is challenging to pull aesthetic discourse from a 7 year old child, but rewarding when one of the kids notices the lack of dynamic lights and darks within the overall image, or if the painting just needs more of a particular color. Providing technical painting lessons throughout the years has enlightened my perspective of what painting can be. Our investment in this body of work goes far beyond what public collaborations with a wide audience and short term interactions can offer. We have been tempted to expand our group to include others, but chosen not to. Our group is invested in each other more than the resulting images and textures of the work. The long term context of this ongoing project truly pushes the boundaries of how art can be integrated into the practice of small to medium sized familial groups.

This work makes use of mostly acrylic paints, some collage, 3d prints, toys, vinyl stickers, and a variety of graphite, charcoal, markers and whatever else these kids could get their hands on. We choose to work on wood panels to hold up to the potential damage that can ensue from intense emotional expressions. The work is backed with a frame of 1/2in by 3in Poplar wood boards to keep the panels sturdy and well-mounted on the walls. We have rarely implemented subtractive processes, outside of removing wet paint, leaving the work to build topographically over time.

We agreed when certain pieces are complete, which has lead to great discourse on why anything is considered finished. These pieces are presented in this body of work as a capstone for the project overall. While we will continue to practice creating images, textures, objects and more as a family, we hope that you enjoy this body of work as an insight to our family.